0 引言

1 材料与方法

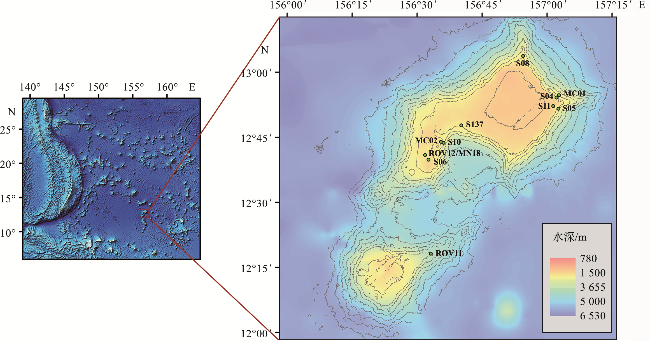

1.1 样品采集

1.2 样品预处理

1.3 稳定同位素分析

2 结果

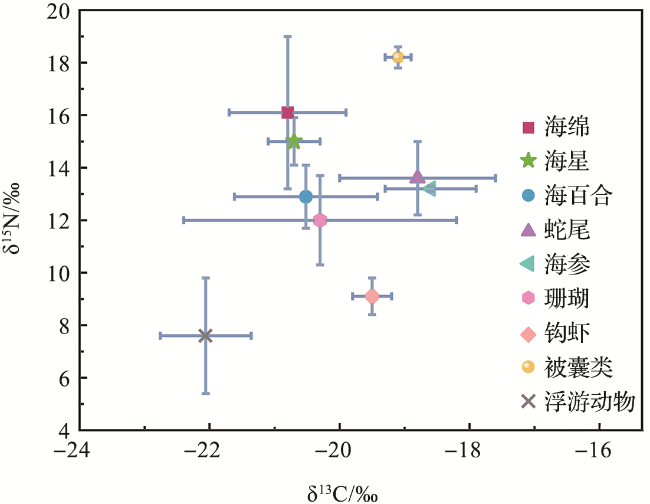

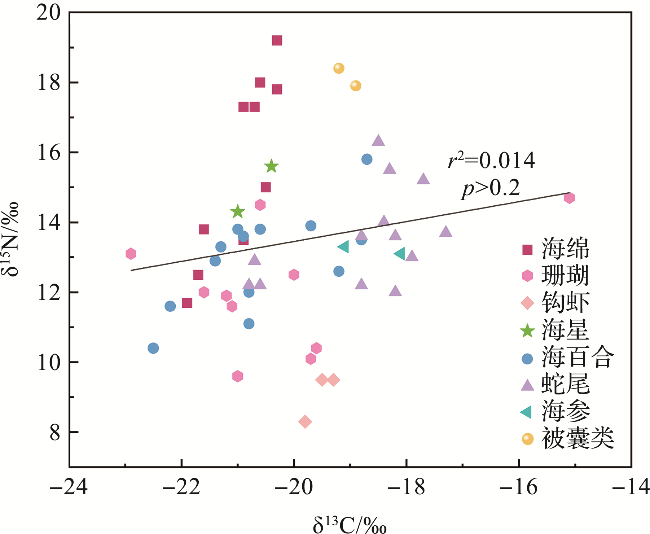

表1 维嘉海山巨型底栖生物各类群的稳定同位素(δ13C和δ15N)值Tab.1 Stable isotope (δ13C and δ15N) values of megabenthos in the Weijia Guyot |

| 底栖生物 | 站位 | 水深/m | δ13C/‰ | δ15N/‰ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 海绵Porifera | ||||

| 勾棘海绵Uncinateridae | S04 | 1 907 | -20.5 (0.1) | 15.0 |

| 绢网海绵Farreidae | S04 | 1 796 | -20.6 (0.2) | 18.0 (0.1) |

| 绢网海绵Farrea sp. | S04 | 1 796 | -20.3 (0.1) | 17.8 (0.1) |

| 长茎海绵Caulophacus sp. | ROV11 | 2 380 | -19.1 | 18.1 (0.1) |

| 长茎海绵Caulophacus sp. | S04 | 1 947 | -20.9 (0.1) | 17.3(0.2) |

| 长茎海绵Caulophacus sp. | S06 | 1 681 | -20.7 | 17.3 |

| 沃尔特海绵Walteria sp. n. HC-2 021 | S04 | 1 850 | -21.7 (0.1) | 12.5 (0.1) |

| 沃尔特海绵Walteria sp. n. HC-2 022 | S06 | 1 702 | -21.9 (0.1) | 11.7 (0.1) |

| 沃尔特海绵Walteria sp. | S10 | 1 941 | -21.6 (0.1) | 13.8 (0.1) |

| 黄绿茎球海绵Flavovirens sp. | S05 | 2 193 | -20.3 | 19.2(0.3) |

| 平均值 | -20.8±0.9 | 16.1±2.9 | ||

| 珊瑚Anthozoa | ||||

| 海笔Protoptilum sp. | S08 | 1 776 | -21.1 | 11.6 (0.2) |

| 半红珊瑚hemicorallium sp. | S08 | 2 076 | -15.1 (0.1) | 14.7 (0.1) |

| 拟柳珊瑚Paragorgia sp. | S04 | 1 796 | -20.0 (0.2) | 12.5 (0.1) |

| 金柳珊瑚Chrysogorgia sp. | S04 | 1 796 | -19.6 | 10.4 (0.1) |

| 金柳珊瑚Chrysogorgia sp. | S04 | 1 796 | -21.0 (0.2) | 9.6 (0.1) |

| 金柳珊瑚Chrysogorgia sp. | S05 | 1 791 | -19.7 (0.2) | 10.1 |

| 角柳珊瑚Keratoisididae | S04 | 1 796 | -21.6 (0.1) | 12.0 (0.1) |

| 角柳珊瑚Keratoisididae | S04 | 1 806 | -21.2 (0.1) | 11.9 (0.2) |

| 角柳珊瑚Keratoisididae | S10 | 1 753 | -22.9 | 13.1 (0.2) |

| 裂黑珊瑚Schizopathidae | S06 | 1 885 | -20.6 (0.1) | 14.5 (0.1) |

| 平均值 | -20.3±2.1 | 12.0±1.7 | ||

| 钩虾Gammaridea | ||||

| 隐首钩虾Stegocephalidae | S137 | 1 985 | -19.3 (0.2) | 9.5 (0.2) |

| 隐首钩虾Stegocephalidae | S137 | 1 985 | -19.5 (0.2) | 9.5 (0.2) |

| 隐首钩虾Stegocephalidae | S137 | 1 985 | -19.8 (0.2) | 8.3 (0.3) |

| 平均值 | -19.5±0.3 | 9.1±0.7 | ||

| 海星Asteroidea | ||||

| 奇板海星Colpaster patricki | S08 | 2 070 | -21.0 (0.1) | 14.3 (0.1) |

| 奇板海星Colpaster patricki | S04 | 1 728 | -20.4 | 15.6 |

| 平均值 | -20.7±0.4 | 15.0±0.9 | ||

| 海百合Crinoidea | ||||

| 奇异羽枝海百合Thaumatocrinus sp.2 | ROV11 | 2 380 | -18.7 (0.2) | 15.8 (0.2) |

| 奈氏奇异羽枝海百合Thaumatocrinus naresi | ROV12 | 1 727 | -19.2 (0.3) | 12.6 (0.3) |

| 奈氏奇异羽枝海百合Thaumatocrinus naresi | ROV12 | 1 702 | -22.2 (0.1) | 11.6 (0.1) |

| 海羊齿海百合Antedonidae gen sp.5 | ROV12 | 1 702 | -18.8 (0.1) | 13.5 (0.3) |

| 海羊齿海百合Antedonidae gen sp.5 | S06 | 1 728 | -21.0 (0.1) | 13.8 (0.1) |

| 海羊齿海百合Antedonidae gen sp.8 | S06 | 1 728 | -19.7 (0.2) | 13.9 (0.1) |

| 海羽枝海百合Thalassometridae gen. sp.2 | S04 | 1 796 | -21.3 (0.1) | 13.3 (0.2) |

| 海羽枝海百合Thalassometridae gen. sp.2 | S04 | 1 796 | -20.8 | 12.0 (0.1) |

| 海羽枝海百合Thalassometra sp. | S06 | 1 728 | -20.6 | 13.8 (0.1) |

| 吉列海百合Guillecrinus cf. neocaledonicus | S08 | 2 101 | -20.9 (0.1) | 13.6 (0.1) |

| 吉列海百合Guillecrinus cf. neocaledonicus | S10 | 1 812 | -21.4 (0.1) | 12.9 (0.2) |

| 穹羽枝海百合Sarametra sp. | S04 | 1 947 | -20.8 (0.1) | 11.1 (0.1) |

| 穹羽枝海百合Sarametra sp. | S06 | 1 681 | -22.5 (0.2) | 10.4 (0.1) |

| 平均值 | -20.6±1.2 | 12.9±1.4 | ||

| 蛇尾Ophiuroidea | ||||

| 德式柱蛇尾Ophiocamax drygalskii | ROV12 | 1 752 | -18.3 (0.1) | 15.5 (0.1) |

| 护盾砖蛇尾Ophioplinthaca defensor | ROV12 | 1 702 | -18.8 (0.1) | 12.2 (0.2) |

| 护盾砖蛇尾Ophioplinthaca defensor | ROV12 | 1 702 | -17.3 (0.3) | 13.7 (0.3) |

| 护盾砖蛇尾Ophioplinthaca defensor | ROV12 | 1 702 | -17.9 (0.2) | 13.0 (0.3) |

| 护盾砖蛇尾Ophioplinthaca defensor | S11 | 1 608 | -18.2 (0.2) | 12.0 |

| 护盾砖蛇尾Ophioplinthaca defensor | S11 | 1 608 | -18.2 (0.1) | 13.6 |

| 护盾砖蛇尾Ophioplinthaca defensor | S08 | 2 070 | -18.8 (0.1) | 13.6 (0.1) |

| 护盾砖蛇尾Ophioplinthaca defensor | S08 | 2 070 | -18.4 (0.2) | 14.0 (0.3) |

| 星蛇尾Asteroschema sp. | S08 | 2 076 | -18.5 (0.2) | 16.3 (0.1) |

| 星蛇尾Asteroschema sp. | S04 | 1 796 | -17.7 (0.1) | 15.2 (0.2) |

| 美丽莱拉蛇尾Ophioleila elegans | S04 | 1 850 | -20.6 (0.1) | 12.2 (0.2) |

| 美丽莱拉蛇尾Ophioleila elegans | S04 | 1 850 | -20.8 (0.2) | 12.2 |

| 美丽莱拉蛇尾Ophioleila elegans | S04 | 1 850 | -20.7 (0.1) | 12.9 (0.1) |

| 平均值 | -18.8±1.2 | 13.6±1.4 | ||

| 海参Holothuroidea | ||||

| 帕劳底游参Benthodytes palauta | S05 | 2 525 | -18.1 (0.2) | 13.1 (0.2) |

| 深海参Benthogone sp. | S10 | 1 820 | -19.1 | 13.3 |

| 平均值 | -18.6±0.7 | 13.2±0.1 | ||

| 被囊类Tunicate | ||||

| 被囊类Tunicate | S08 | 2 101 | -18.9 | 17.9 (0.1) |

| 被囊类Tunicate | S08 | 2 157 | -19.2 (0.1) | 18.4 (0.2) |

| 平均值 | -19.1±0.2 | 18.2±0.4 |

注:括号中数字为重复测量的标准差,加粗字体为平均值。 |

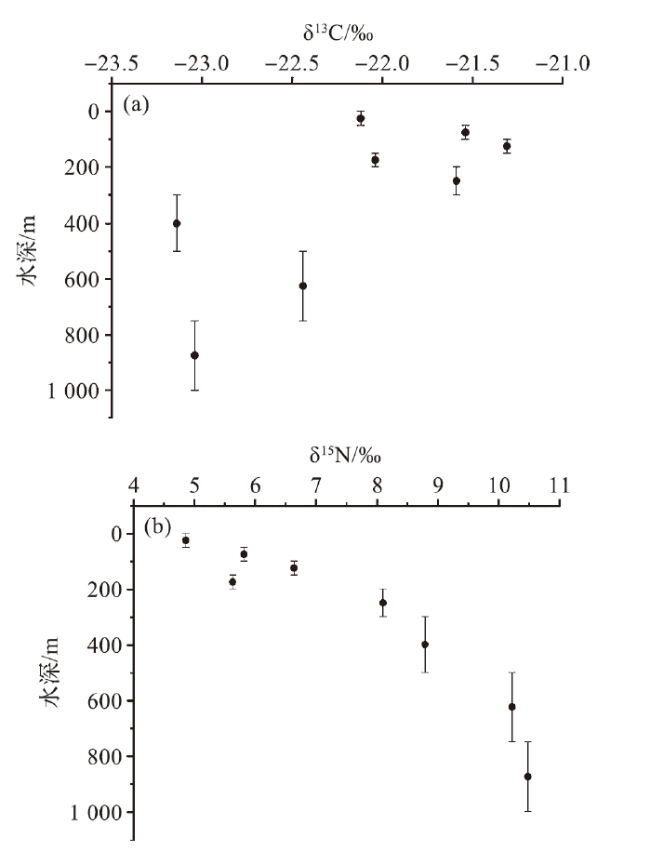

表2 浮游动物的稳定同位素(δ13C和δ15N)值Tab.2 Stable isotope (δ13C and δ15N) values of zooplankton |

| 站位 | 水深/m | δ13C/‰ | δ15N/‰ |

|---|---|---|---|

| MN18 | 0~50 | -22.1 | 4.9 |

| MN18 | 50~100 | -21.5 | 5.8 |

| MN18 | 100~150 | -21.3 | 6.6 |

| MN18 | 150~200 | -22.0 | 5.6 |

| MN18 | 200~300 | -21.6 | 8.1 |

| MN18 | 300~500 | -23.1 | 8.8 |

| MN18 | 500~750 | -22.4 | 10.2 |

| MN18 | 750~1 000 | -23.0 | 10.5 |

| 平均值 | -22.1±0.7 | 7.6±2.2 |

图3 浮游动物δ13C (a) 和 δ15N (b)的垂直分布Fig.3 Vertical distribution of δ13C (a) and δ15N (b) for zooplankton |

表3 表层沉积物的稳定同位素(δ15N)值Tab.3 Stable isotope (δ15N) values of surface sediments |

| 站位 | 水深/m | δ15N/‰ |

|---|---|---|

| MC01 | 2 351 | 7.7(0.2) |

| MC02 | 2 512 | 7.7(0.1) |

| 平均值 | 7.7 |